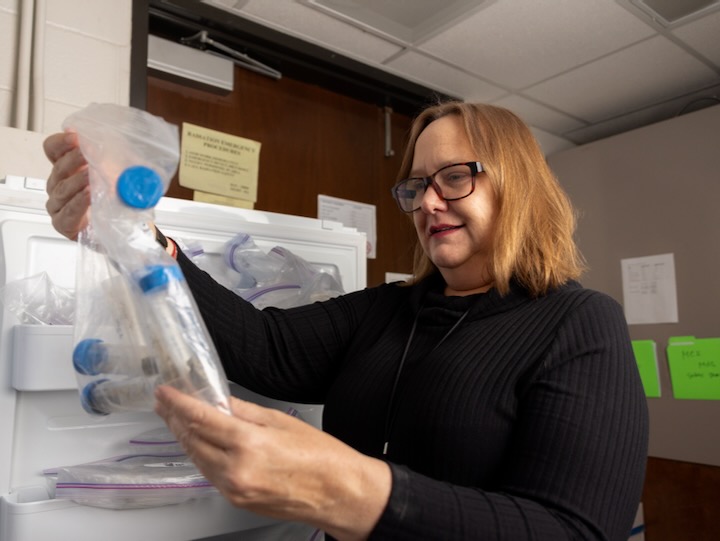

On a 2019 expedition to the Amundsen Sea in Antarctica (pictured), a University of Houston scientist led a team that collected a marine sediment sample from more than 3 million years ago. This sample could helps researchers study glacier history and predict how they may respond to environmental shifts. (Credit Phil Christie, SIEM Offshore)

Key Takeaways

- Ancient sediment records collected by a University of Houston researcher show that the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers repeatedly retreated during past warm periods, including sudden collapses after long phases of slow retreat.

- The findings suggest that major parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are highly sensitive to warming and could drive rapid sea-level rise as global temperatures increase.

- The study is based on irreplaceable Antarctic sediment cores collected during a rare offshore drilling expedition, providing the only known Pliocene record of this glacial drainage area.

A University of Houston researcher is part of an international team investigating significant melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, research that reconstructs ice-sheet behavior from millions of years ago to better predict how they may respond to future climate patterns or environmental shifts.

A new study published Dec. 22 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers — key components of the WAIS — receded at least five times during the Pliocene, approximately 3 to 4.5 million years ago.

Led by Keiji Horikawa, professor at the University of Toyama in Japan, the research team analyzed marine sediments deposited by the glaciers. The samples were collected through an offshore expedition in 2019 and represent the only known geological record of this glacial sector from the Pliocene.

The geological record provides crucial insight into how the ice sheet may behave in the future as environmental patterns shift and temperatures rise. It also raises concerns about the potential for rapid sea-level rise if large parts of the WAIS were to collapse again, said Julia Wellner, professor of glacial and marine geology at UH and a co-author on the report.

“What this sediment core has shown is that there was major inland retreat of Thwaites during these time periods,” Wellner said. “More significant than that, it also shows the glacier retreats pretty slowly and then reaches the final pulse where it's going to pull back very suddenly.”

Why It Matters

Scientists focused on the Pliocene because global temperatures at the time were similar to or slightly warmer than today. This makes it a more useful comparison for climate projections than the last interglacial period roughly 120,000 years ago.

“If we want to know what can happen in more extreme warming, we need to go back to times like the Pliocene, to a warmer environment,” Wellner said. “In recent times, the planet has warmed to a point that if we just look at the last interglacial period, it’s no longer comparable.”

The melting of grounded ice — glaciers and ice sheets that rest on land rather than float in water — directly contribute to global sea-level rise. While sea level is already rising and accelerating, the new geological record shows that it can rise much faster than modern society has experienced.

“The background reasoning for everything I do is to get a better understanding on how fast and how much will sea level rise,” Wellner said. “While we don't have all of the answers, what we can definitively say is it is too fast and too much.”

Sampling a Piece of History

Wellner first studied the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers as a graduate researcher in 1999. Twenty years later, Wellner returned to the Amundsen Sea as co-chief scientist, leading a major international offshore drilling expedition with German researcher Karsten Gohl.

“I definitely have a soft spot for working at Thwaites and Pine Island,” Wellner said. “They are important parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, and understanding them, I believe, is of critical importance.”

Unlike modern ice changes, which are primarily tracked by satellite over the past 50 years, older glacial history must be reconstructed from sediments collected beneath ice sheets or from the seafloor. Offshore sediment collection is less invasive than drilling through ice but comes with logistical challenges.

The Amundsen Sea is extremely remote and difficult to access, as it is far from any staging landmass. Scientists worked from a non-icebreaking drill ship in waters about 4,000 meters deep, drilling up to 800 meters below the seafloor while constantly maneuvering to avoid icebergs.

The 2019 expedition was funded by the International Ocean Discovery Program, which was a program of the U.S. and several other countries that ended in 2024, making the cores irreplaceable. The cores are stored at a federal repository at Texas A&M University that will remain open despite the end of the drilling program.

“This sample is rarer than a moon rock,” Wellner said. “If we want to know about the West Antarctic during this time period, these are the samples to do it — there are no backup samples.”

Researchers analyzed the geochemical signatures of the sediment, particularly isotopes of strontium, neodymium and lead. These markers revealed where the particles originated on the Antarctic continent, helping scientists determine when ice covered specific regions and reconstruct past ice-sheet extent.

Although the International Ocean Discovery Program has ended, the Pliocene sediment cores will continue to be studied for years. Wellner already has additional papers under review and expects several more publications. The PNAS study provides the foundation for that future work.

Meanwhile, Wellner serves as the lead scientist for Thwaites Offshore Research, which examines glacier behavior over the past 100-200 years. Using shallow sediment cores and laboratory dating methods, her team reconstructs glacier behavior before satellite observations began, helping bridge the gap between modern data and deep geological history.